Bill Russell is not only the greatest winner in sports history – the man who won 55 consecutive games and two NCAA titles at the University of San Francisco, took a gold medal at the 1956 Olympic Games, and led the Boston Celtics to 11 NBA championships. Russell also initiated the transformation of basketball’s place in American culture. He became basketball’s first black superstar. His leaping, wide-ranging defense altered the game’s texture. As a generation of African-American stars followed in his footsteps, basketball and blackness intertwined in the popular imagination. His USF Dons and Boston Celtics acted as the sport’s models of racial integration in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1966 Russell became the first black coach of any major professional team sport. In these same years, the NBA grew from a sweaty, regional “bush league” into a lucrative, national “big league”.

Yet, like no athlete before him, Russell challenged the politics of sport. In an era when black athletes were supposed to display appreciative deference, he underwent an agonizing personal crisis. He started decrying racist institutions, embracing his African roots, and challenging the nonviolent tenets of the civil rights movement. While crumbling basketball’s racial barriers, he foreshadowed the “Revolt of the Black Athlete.” His courage forced sports fans to consider him as more than a social symbol. He demanded recognition as a complicated individual, one who expressed the dreams of Martin Luther King while echoing the warnings of Malcolm X.

Yet, like no athlete before him, Russell challenged the politics of sport. In an era when black athletes were supposed to display appreciative deference, he underwent an agonizing personal crisis. He started decrying racist institutions, embracing his African roots, and challenging the nonviolent tenets of the civil rights movement. While crumbling basketball’s racial barriers, he foreshadowed the “Revolt of the Black Athlete.” His courage forced sports fans to consider him as more than a social symbol. He demanded recognition as a complicated individual, one who expressed the dreams of Martin Luther King while echoing the warnings of Malcolm X.

King of the Court: Bill Russell and the Basketball Revolution chronicles the life and career of this champion athlete, racial pioneer, and fascinating personality. Russell invested enormous significance in winning championships, yet he fretted about his social utility as an athlete. He cherished his bonds with both white and black teammates, yet he radiated defiance of white expectations. He developed a strong self-pride independent of sports, but part of him always remained the awkward, bookish child who missed his dead mother.

Russell first ushered college basketball into its modern age. His USF teams delivered his sport a truly national profile, a more dynamic style of play, and a harbinger of racial integration. No major program had ever started three black players, but USF coach Phil Woolpert recruited and started Russell, K.C. Jones, and Hal Perry. Despite racist harassment, these men provided the foundation for a 55-game winning streak that started in December 1954 and ended in March 1956, after USF had won its second consecutive NCAA championship. Before the USF streak, a snapshot of big-time college basketball revealed white players focused upon deliberate, earthbound offensive patterns; after the streak, college programs began featuring racially integrated units that placed a premium on speed and aggressive defense.

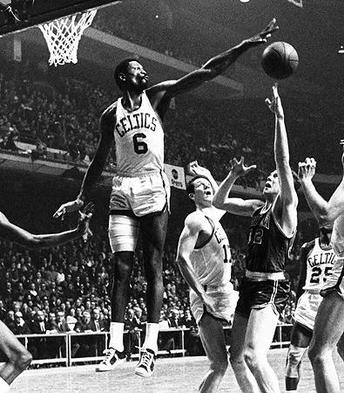

Russell played defense the way Picasso painted, the way Hemingway wrote: in time, he changed how people understood the craft. He bucked conventional wisdom by leaping to block shots, lending a new element of intimidation. When he led the United States to a gold medal at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, the Soviets marveled at his rangy, springy style. Back at home, traditionalists still questioned whether Russell’s talents translated to the physical pro game. Russell destroyed those doubts. Despite scoring talents such as Bob Cousy and Bill Sharman, the Boston Celtics had never won an NBA title. Then Russell started sucking down rebounds, scaring rival shooters, and triggering the fast break. Boston won a title in his rookie year. Russell won MVP in his second year. Then another title followed, and another, and another, and another. . . . In Russell’s 13 professional seasons between 1956 and 1969, the Boston Celtics won an astonishing 11 championships. Fourteen times, his season boiled down to one winner-take-all game. Fourteen times, Russell’s team won.

Russell first ushered college basketball into its modern age. His USF teams delivered his sport a truly national profile, a more dynamic style of play, and a harbinger of racial integration. No major program had ever started three black players, but USF coach Phil Woolpert recruited and started Russell, K.C. Jones, and Hal Perry. Despite racist harassment, these men provided the foundation for a 55-game winning streak that started in December 1954 and ended in March 1956, after USF had won its second consecutive NCAA championship. Before the USF streak, a snapshot of big-time college basketball revealed white players focused upon deliberate, earthbound offensive patterns; after the streak, college programs began featuring racially integrated units that placed a premium on speed and aggressive defense.

Russell played defense the way Picasso painted, the way Hemingway wrote: in time, he changed how people understood the craft. He bucked conventional wisdom by leaping to block shots, lending a new element of intimidation. When he led the United States to a gold medal at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, the Soviets marveled at his rangy, springy style. Back at home, traditionalists still questioned whether Russell’s talents translated to the physical pro game. Russell destroyed those doubts. Despite scoring talents such as Bob Cousy and Bill Sharman, the Boston Celtics had never won an NBA title. Then Russell started sucking down rebounds, scaring rival shooters, and triggering the fast break. Boston won a title in his rookie year. Russell won MVP in his second year. Then another title followed, and another, and another, and another. . . . In Russell’s 13 professional seasons between 1956 and 1969, the Boston Celtics won an astonishing 11 championships. Fourteen times, his season boiled down to one winner-take-all game. Fourteen times, Russell’s team won.

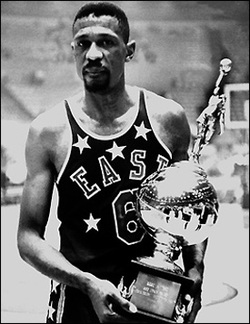

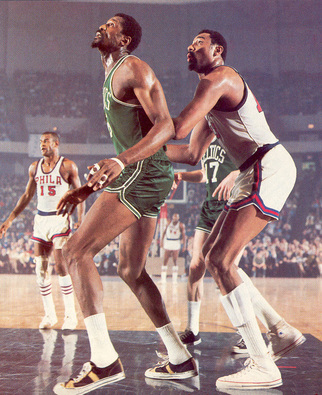

“I should epitomize the American Dream,” Russell wrote in Sports Illustrated, soon after retiring in 1969. He had won five MVP awards. He had cherished his collaborations with coach Red Auerbach and his fellow Celtics, whose unselfishness transmitted the spirit of interracial cooperation. His rivalry with Wilt Chamberlain had lent the NBA its pre-eminent narrative, and Russell appeared the hero for constantly repelling his physically stronger, psychologically weaker opponent. He had pioneered the league’s transition from overwhelmingly white to predominantly black. He had helped the NBA attract national television contracts, pay high salaries, expand across the nation, and generally become the third major American team sport. He had served as player-coach for his last two titles, both of which involved improbable triumphs over Chamberlain’s superior squads. He had earned wealth, fame, and respect.

But Russell wrote that he should embody the spirit of democracy. He underwent periods of serious crisis, where he questioned his social worth. He sought to transcend basketball, both in his personal and political life. He often traveled to Africa, where he bought a Liberian rubber plantation. He immersed himself in the black freedom struggle, journeying to Mississippi during the dangerous “Freedom Summer” of 1964 and becoming the most visible critic of Boston’s racist patterns and attitudes. Throughout the 1960s, he aired disenchantment with racial double standards and institutional hypocrisies. He defended the Nation of Islam, claimed to dislike most white people, accused the NBA of a white quota system, refused to sign autographs, and adopted a scowling, regal demeanor. In an age when black public figures exhibited humility, Russell expected respect. He was a kingly sports icon, feared by many whites and adored by most blacks.

Russell’s story thus reveals the courage of a black athlete who, while the game’s most respected figure, also served as its most visible public intellectual. During his reign basketball underwent meaningful changes: a stylistic evolution, a financial expansion, a new standard of team excellence, and a racial upheaval. These changes arrived gradually and imperfectly, but together they transformed the sport’s meaning in American culture. Call it the basketball revolution – and place Bill Russell at its center.

But Russell wrote that he should embody the spirit of democracy. He underwent periods of serious crisis, where he questioned his social worth. He sought to transcend basketball, both in his personal and political life. He often traveled to Africa, where he bought a Liberian rubber plantation. He immersed himself in the black freedom struggle, journeying to Mississippi during the dangerous “Freedom Summer” of 1964 and becoming the most visible critic of Boston’s racist patterns and attitudes. Throughout the 1960s, he aired disenchantment with racial double standards and institutional hypocrisies. He defended the Nation of Islam, claimed to dislike most white people, accused the NBA of a white quota system, refused to sign autographs, and adopted a scowling, regal demeanor. In an age when black public figures exhibited humility, Russell expected respect. He was a kingly sports icon, feared by many whites and adored by most blacks.

Russell’s story thus reveals the courage of a black athlete who, while the game’s most respected figure, also served as its most visible public intellectual. During his reign basketball underwent meaningful changes: a stylistic evolution, a financial expansion, a new standard of team excellence, and a racial upheaval. These changes arrived gradually and imperfectly, but together they transformed the sport’s meaning in American culture. Call it the basketball revolution – and place Bill Russell at its center.