About The Men and the Moment

Throughout the presidential election of 1968, the backdrop was chaos. In February of that year, communist forces launched the Tet Offensive, intensifying questions about the U.S. role in the Vietnam War. In April, Martin Luther King was assassinated, triggering fury and angst among African Americans as well as terrible riots in inner cities. Later that month, the nation’s cultural divide sharpened when radical students occupied buildings at Columbia University and the police brutally removed them. That summer, the Cold War hardened with the Soviet Union’s ruthless invasion of Czechoslovakia. On the streets outside the Democratic National Convention, the Chicago police attacked peace activists, and the nation appeared to descend into political pandemonium. By Election Day that November, many Americans were questioning the basic stability of their core institutions.

That anxiety helps explain voters’ choices. The 1968 election shaped the identities of our two major political parties. It signaled the end of a long liberal era in American politics, beginning with the New Deal of the 1930s. The Democratic coalition—which included the urban working class, African Americans, intellectuals, and white southerners—met its demise. The party has since struggled to advocate progressive policies while capturing the political center. Just as important, the election mobilized the conservative forces that dominated the era to come. The Republican Party resonated with the comfortable-yet-nervous middle class, spreading into the growing suburbs and the emerging South, while learning to absorb an emerging populist conservatism.

The presidential campaign of 1968 was a last hurrah for the “Old Politics,” in which political machines and party leaders determined the major nominees. It also highlighted a “New Politics,” in which candidates took their cases right to the people, through party primaries and modern technology. On both the Left and Right, candidates seized hot-button issues to alter the larger political dynamic. And more than any previous campaign, it showcased the transformative power of television to “package” candidates.

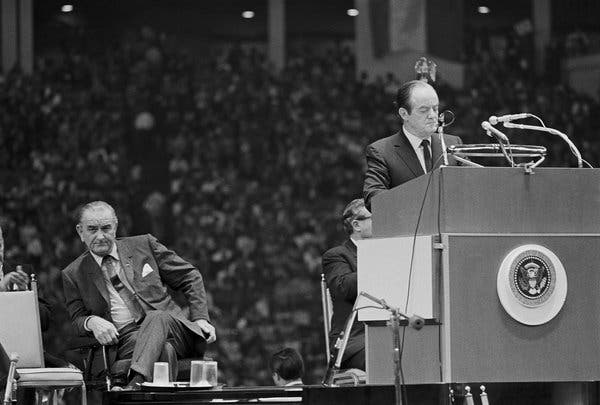

The candidates were extraordinary personalities. The Democrats battled for the soul of their party. Like a cunning, tortured king out of Shakespeare, Lyndon Johnson presided over the action, even after his shocking decision not to seek reelection. Eugene McCarthy was the rallying figure for a remarkable grassroots campaign rooted in opposition to the Vietnam War, even as he sabotaged his prospects through his diffidence. Bobby Kennedy, both adored and despised, was evolving from his brother’s prickly lieutenant into a charismatic hero of common folk, only to die at the hands of an assassin. Hubert Humphrey, bullied into servility as Johnson’s vice president, needed an independent strategy on the Vietnam War to finally become his “own man.”

On the Republican side, the magnetic figures of Nelson Rockefeller and Ronald Reagan pulled on the left and right wings, respectively, of the party. Meanwhile, the fiery George Wallace almost toppled the two-party system with his aggressive politics of reactionary resentment. But it was Richard Nixon who found the language of the Republican resurgence: “law and order” to contain urban violence, patriotic vagueness on Vietnam, and appeals to “forgotten Americans” who resented the Great Society’s devotion of resources to the poor, oppressed, and black. By winning the presidency, Nixon completed the greatest comeback in modern American political history. Only Nixon committed to running throughout the election cycle. Only Nixon calculated an approach of pragmatism over principle. Only Nixon exploited all the tools available to him—from slick television ads to diplomatic deception. His narrow victory, accomplished by dubious means, laid the foundation for the crisis that ultimately befell him.

As you might imagine, many books describe the presidential election of 1968. In its immediate aftermath, journalists from the United States and Great Britain wrote long, detailed, insightful accounts. Popular writers have described the election alongside trends in American culture and developments around the globe. Excellent biographies, enhanced by archival research and personal interviews, depict all the major candidates. Political scientists have analyzed electoral strategies and party processes. Academic historians have contextualized the election through studies of grassroots politics.

The Men and the Moment seeks to pull together these strands into a short, engaging narrative. It relies on the research and insights of many authors, along with the profuse output of political journalists during that hectic year. Each of the first eight chapters centers upon a single candidate, and the chapters toggle back and forth between Democrats and Republicans (until the chapter on George Wallace, who ran under the banner of the American Independent Party). Though the book moves forward through 1968, the chapters often cover overlapping developments. A timeline of major events, found in the appendix, can help keep the story straight.

The echoes of 1968 reverberate in our contemporary politics. We again have flamboyant demagogues who conjure fears of elite conspiracies, righteous progressives who seek to reclaim the ideals of the Democratic Party, liberal centrists who fail to summon a unifying message, and accusations of foreign interference in our democratic process. My hope is that readers can draw those parallels, yet understand the election of 1968 within its special context—particularly through the personal experiences of each candidate. These were all elite, influential white men in late adulthood. At times, they were put to the test. As the book and chapter titles illustrate, their notions of manhood shaped their political identities—sometimes in overt ways and at other times more subtly. But gender roles and expectations, on their own, cannot explain the presidential election of 1968. Each candidate was responding to the swirling forces of that tumultuous year, acting in a specific historical moment. Their critical decisions, which altered the nation’s destiny, were shaped by their personal backstories, their public images, and their political odysseys.

That anxiety helps explain voters’ choices. The 1968 election shaped the identities of our two major political parties. It signaled the end of a long liberal era in American politics, beginning with the New Deal of the 1930s. The Democratic coalition—which included the urban working class, African Americans, intellectuals, and white southerners—met its demise. The party has since struggled to advocate progressive policies while capturing the political center. Just as important, the election mobilized the conservative forces that dominated the era to come. The Republican Party resonated with the comfortable-yet-nervous middle class, spreading into the growing suburbs and the emerging South, while learning to absorb an emerging populist conservatism.

The presidential campaign of 1968 was a last hurrah for the “Old Politics,” in which political machines and party leaders determined the major nominees. It also highlighted a “New Politics,” in which candidates took their cases right to the people, through party primaries and modern technology. On both the Left and Right, candidates seized hot-button issues to alter the larger political dynamic. And more than any previous campaign, it showcased the transformative power of television to “package” candidates.

The candidates were extraordinary personalities. The Democrats battled for the soul of their party. Like a cunning, tortured king out of Shakespeare, Lyndon Johnson presided over the action, even after his shocking decision not to seek reelection. Eugene McCarthy was the rallying figure for a remarkable grassroots campaign rooted in opposition to the Vietnam War, even as he sabotaged his prospects through his diffidence. Bobby Kennedy, both adored and despised, was evolving from his brother’s prickly lieutenant into a charismatic hero of common folk, only to die at the hands of an assassin. Hubert Humphrey, bullied into servility as Johnson’s vice president, needed an independent strategy on the Vietnam War to finally become his “own man.”

On the Republican side, the magnetic figures of Nelson Rockefeller and Ronald Reagan pulled on the left and right wings, respectively, of the party. Meanwhile, the fiery George Wallace almost toppled the two-party system with his aggressive politics of reactionary resentment. But it was Richard Nixon who found the language of the Republican resurgence: “law and order” to contain urban violence, patriotic vagueness on Vietnam, and appeals to “forgotten Americans” who resented the Great Society’s devotion of resources to the poor, oppressed, and black. By winning the presidency, Nixon completed the greatest comeback in modern American political history. Only Nixon committed to running throughout the election cycle. Only Nixon calculated an approach of pragmatism over principle. Only Nixon exploited all the tools available to him—from slick television ads to diplomatic deception. His narrow victory, accomplished by dubious means, laid the foundation for the crisis that ultimately befell him.

As you might imagine, many books describe the presidential election of 1968. In its immediate aftermath, journalists from the United States and Great Britain wrote long, detailed, insightful accounts. Popular writers have described the election alongside trends in American culture and developments around the globe. Excellent biographies, enhanced by archival research and personal interviews, depict all the major candidates. Political scientists have analyzed electoral strategies and party processes. Academic historians have contextualized the election through studies of grassroots politics.

The Men and the Moment seeks to pull together these strands into a short, engaging narrative. It relies on the research and insights of many authors, along with the profuse output of political journalists during that hectic year. Each of the first eight chapters centers upon a single candidate, and the chapters toggle back and forth between Democrats and Republicans (until the chapter on George Wallace, who ran under the banner of the American Independent Party). Though the book moves forward through 1968, the chapters often cover overlapping developments. A timeline of major events, found in the appendix, can help keep the story straight.

The echoes of 1968 reverberate in our contemporary politics. We again have flamboyant demagogues who conjure fears of elite conspiracies, righteous progressives who seek to reclaim the ideals of the Democratic Party, liberal centrists who fail to summon a unifying message, and accusations of foreign interference in our democratic process. My hope is that readers can draw those parallels, yet understand the election of 1968 within its special context—particularly through the personal experiences of each candidate. These were all elite, influential white men in late adulthood. At times, they were put to the test. As the book and chapter titles illustrate, their notions of manhood shaped their political identities—sometimes in overt ways and at other times more subtly. But gender roles and expectations, on their own, cannot explain the presidential election of 1968. Each candidate was responding to the swirling forces of that tumultuous year, acting in a specific historical moment. Their critical decisions, which altered the nation’s destiny, were shaped by their personal backstories, their public images, and their political odysseys.