Backstory of Down to the Crossroads

For me, researching and writing Down to the Crossroads revolved around one key question: How do you tell the story of the civil rights movement?

When I first started reading about the civil rights movement, I learned mostly about Martin Luther King, nonviolent protests, and brutal southern racists. I saw how civil rights leaders captured the attention of the federal government during dramatic flashpoints publicized by the media, leading to national legislation that wove black people into the fabric of American democracy. In this telling, there were great triumphs. Then, with Black Power and urban riots, things fell apart. This narrative roughly spans from the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 to King’s assassination in 1968. There is great narrative power in these accounts, and they convey important themes about the movement’s drama and importance. But you might call it the “old” civil rights history.

The “new” civil rights history challenges this tale. Starting in graduate school and then especially as I was leading graduate seminars while teaching at the University of Memphis, I better appreciated the contributions of a few generations of scholars who have complicated how we think about the black freedom struggle. By examining local movements, they reveal the importance of grassroots activists, especially women, and show that few African Americans practiced nonviolence in the vein of Martin Luther King. They also see a “long civil rights movement” that stretched back before World War II, continued into contemporary battles for social change, and stretched beyond the South. Some historians place the movement in the international context of the Cold War and African independence movements, and others concentrate on the complex ways that white southerners responded to civil rights challenges, with some of those strategies connecting to national conservative trends. Finally, the emerging field of “Black Power Studies” emphasizes the deep roots of this political philosophy, celebrates its affirmation of black identity, and considers its potent influence upon American democracy.

When I first started reading about the civil rights movement, I learned mostly about Martin Luther King, nonviolent protests, and brutal southern racists. I saw how civil rights leaders captured the attention of the federal government during dramatic flashpoints publicized by the media, leading to national legislation that wove black people into the fabric of American democracy. In this telling, there were great triumphs. Then, with Black Power and urban riots, things fell apart. This narrative roughly spans from the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 to King’s assassination in 1968. There is great narrative power in these accounts, and they convey important themes about the movement’s drama and importance. But you might call it the “old” civil rights history.

The “new” civil rights history challenges this tale. Starting in graduate school and then especially as I was leading graduate seminars while teaching at the University of Memphis, I better appreciated the contributions of a few generations of scholars who have complicated how we think about the black freedom struggle. By examining local movements, they reveal the importance of grassroots activists, especially women, and show that few African Americans practiced nonviolence in the vein of Martin Luther King. They also see a “long civil rights movement” that stretched back before World War II, continued into contemporary battles for social change, and stretched beyond the South. Some historians place the movement in the international context of the Cold War and African independence movements, and others concentrate on the complex ways that white southerners responded to civil rights challenges, with some of those strategies connecting to national conservative trends. Finally, the emerging field of “Black Power Studies” emphasizes the deep roots of this political philosophy, celebrates its affirmation of black identity, and considers its potent influence upon American democracy.

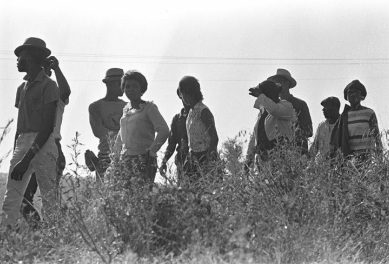

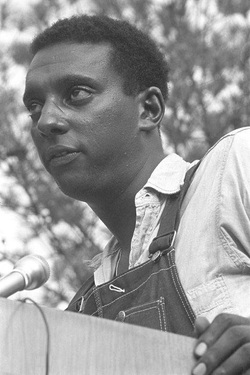

The march through Mississippi in June of 1966 tells “old” and “new” stories about the civil rights movement. Called both the Meredith March and the March Against Fear, it was an operatic drama, full of glorious triumphs and deep despair. It featured the giants of black politics grappling over control and strategy. It starred Martin Luther King, revealing him at his most morally powerful, even as he struggled to unite leaders and stoke the American conscience, rendering him vulnerable and despondent. The march further showcased Stokely Carmichael, the charismatic prophet of Black Power. When Carmichael unveiled the incendiary slogan midway through the march, it did seem to signal the end of an era: a demise for nonviolence, a liberal anxiety, a surging black anger. Black activists had never attempted a more ambitious demonstration, but it was the movement’s last great march.

The Meredith March is familiar to many historians – it occupies a chapter in various civil rights histories and biographies. But I thought this milestone deserved a longer, deeper look. As I got into newspaper accounts and archival material, I learned more about how, as masses of people rambled down country towns and arrived in the squares of Mississippi’s small towns, they demanded their rights as American citizens, unsettling the local patterns of race relations. It was a big march getting national and international attention, but it depended upon the politics of small communities, the resolve of black Mississippians, and the strategies of white officials. The march thus reveals the civil rights movement as both local and national.

This story also shows how Black Power was more than a bogeyman of black rage. It was an outgrowth of the civil rights movement – it demanded that black people control black communities, expressed pride in black culture and history, built on a legacy of thinkers such as Malcolm X, and considered race and democracy in international terms. Of course, the slogan also dramatized disaffection from national politics and white liberals. Black Power was both constructive and destructive, both hopeful and cynical, both unifying and alienating. Its many meanings and manifestations capture the complexity of the black freedom struggle, especially as the movement emerged from the crucible of the March Against Fear.

The Meredith March is familiar to many historians – it occupies a chapter in various civil rights histories and biographies. But I thought this milestone deserved a longer, deeper look. As I got into newspaper accounts and archival material, I learned more about how, as masses of people rambled down country towns and arrived in the squares of Mississippi’s small towns, they demanded their rights as American citizens, unsettling the local patterns of race relations. It was a big march getting national and international attention, but it depended upon the politics of small communities, the resolve of black Mississippians, and the strategies of white officials. The march thus reveals the civil rights movement as both local and national.

This story also shows how Black Power was more than a bogeyman of black rage. It was an outgrowth of the civil rights movement – it demanded that black people control black communities, expressed pride in black culture and history, built on a legacy of thinkers such as Malcolm X, and considered race and democracy in international terms. Of course, the slogan also dramatized disaffection from national politics and white liberals. Black Power was both constructive and destructive, both hopeful and cynical, both unifying and alienating. Its many meanings and manifestations capture the complexity of the black freedom struggle, especially as the movement emerged from the crucible of the March Against Fear.

Most important, the march was about people. I absorbed this lesson over time, as I was conducting interviews with 100 people, almost all of whom directly participated in the march. I interviewed civil rights veterans, black and white, with a wide variety of perspectives on the movement. I talked to organizational leaders, hardened activists, black Mississippi natives, white college students, and a host of others. Their stories gave the march a personal, on-the-ground dimension that I tried to incorporate into the book.

This story belongs to King and Carmichael, but it also belongs to its iconoclastic namesake, James Meredith. It belongs to the unsung hero Floyd McKissick, and it belongs to leaders in Mississippi and Memphis. It belongs, as well, to the local black women who lent the march its backbone. It belongs to anyone who summoned the courage to march alongside the “Freedom Riders” parading through their towns. It belongs to the tough, committed activists mapping out new stages of grassroots organizing; the idealistic white volunteers seeking a place in the movement; the black politicians battling for a seat at Mississippi’s table; the spiritual folk marching out of conscience; the young people envisioning better days ahead; the old people overcoming the fears of a terror-soaked past. It belongs, even, to the whites of Mississippi, whose resistance took both brutal and subtle forms, and to President Lyndon Johnson, brooding just off-stage throughout the drama, consumed by Vietnam and sulking amidst a backlash.

I tried to tell the story of the Meredith March through this kaleidoscope of perspectives. That way, these three weeks in Mississippi refract a broader story about the civil rights movement.

This story belongs to King and Carmichael, but it also belongs to its iconoclastic namesake, James Meredith. It belongs to the unsung hero Floyd McKissick, and it belongs to leaders in Mississippi and Memphis. It belongs, as well, to the local black women who lent the march its backbone. It belongs to anyone who summoned the courage to march alongside the “Freedom Riders” parading through their towns. It belongs to the tough, committed activists mapping out new stages of grassroots organizing; the idealistic white volunteers seeking a place in the movement; the black politicians battling for a seat at Mississippi’s table; the spiritual folk marching out of conscience; the young people envisioning better days ahead; the old people overcoming the fears of a terror-soaked past. It belongs, even, to the whites of Mississippi, whose resistance took both brutal and subtle forms, and to President Lyndon Johnson, brooding just off-stage throughout the drama, consumed by Vietnam and sulking amidst a backlash.

I tried to tell the story of the Meredith March through this kaleidoscope of perspectives. That way, these three weeks in Mississippi refract a broader story about the civil rights movement.